1 Between a Crescent and a Cross

Enlightenment and education

Until the seventh decade of the 18th century, education and literature were under the auspices of the church. Following reforms, which were carried out by the Austrian Emperor Joseph II, a philosophical criticism of reality and the praise of science and knowledge started to be apparent in culture. In keeping with this, instructions for schools, education and educational methods were adopted.

This transitional moment in Serbian culture was personified by Dositej Obradovic (1742–1811), the first Serbian rationalist. Feeling the significance of events in Serbia, he came to Belgrade in 1807. He was the adviser and secretary to Karadjordje, the tutor of his son and the founder of the Great School (1808) and Seminary (1810), and a member of the Executive Soviet, minister of education and the founder of a school in Serbian literature. His followers shared the same ideas, influences and spiritual aspirations. They were all anti-traditionalists, anti-clericalists and wrote using the national language. Some of Dositej’s most significant pupils and followers were: Jovan Muskatirovic, Serbia’s first lawyer, Atanasije Stojkovic, founder of the first physics and the first novelist, Joakim Vujic, “the father of Serbia’s theater.”

Following the dissolution of romanticism, Serbian culture returned to rationalistic ideas.

| << previous The military border | >> next chapter Serbian revolution |

The military border

The Serbs who fled from their captured country continued to fight against the Turks in the territory of Hungary, Austria and the Venetian Republic. They inhabited the Military Border, which Austrian rulers from parts of Croatian lands had organized militarily as protection against the Turks.

The Military Border area was continually expanded and there were a number of such areas. The military district from the coast to the Kupa with Zumberak made up the Croatian Border Area which was named after its seat, Karlovac general headquarters and followed by the Coastal Border Area, which spread from the coast to Kapele and dependant on the Karlovac general headquarters; Banska Border Area from Karlovac to Invanic to the Drava River, afterwards also known as the Varazdin general headquarters.

The villages encompassed within the Military Border had no obligations towards the Croatian feudal lords since their contribution towards the state was its warriors and in the administrative sense, they were subjugated to the ruler as their supreme commander. In 1630 the “Vlaski Statute” (Statuta Valachorum) officially recognized certain privileges for the Serbs in order to establish a more liberal and peaceful life for them. In the 18th century there were 30 attempts to regulate and make the border area more contemporary, which shows that Austria was unable to find a final solution. The Military Border was demilitarized in 1873.

The life of the border guards developed into an endless battlefield where they often clashed not only with the Turks but also with the Croatian gentry, which found it hard to renounce its revenues from the border village estates. The border area soldiers were settled into wooden fortresses joined by enclosed porches. The border guards warned others of imminent danger with shots fired from the enclosed porches. The houses were made of wood, covered with mud and straw or reed mace and cane. They had one room without a floor, which served as a room, kitchen and stall. The hearth was situated in the middle, which was used for cooking and heating. Filed along the walls were wooden beds covered with straw.

The best looking houses belonged to the clergy and officers. Their houses had a number of rooms, a kitchen and auxiliary rooms, and they also had built-in furnaces. Those furnaces were made of clay tiles, made up of a hundred to two hundred pieces with openings towards the rooms.

| << previous Two cities - two empires | >> next Enlightenment and education |

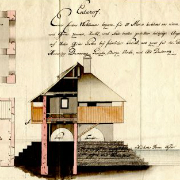

The war times

Belgrade fell under the Turkish rule on 28th august 1521 during the reign of Suleiman II Magnificent. E xcept for а short period of the Austrian rule, Belgrade remained а part of the Turkish empire until the XIX century, as kadiluk of the Smederevo sandzak and, beside the Buda, served as the biggest weapons warehouse in the European part of the Turkey. The population, composed of Serbs, Turks, newcomers from Dubrovnik, Jews, Jermens, Gypsies and others, wаs occupied with the fishing, agriculturing, trading and craftsmenship. The town was decorated with the towers, churches, mosques, and caravan sarays. Islam played a significant role in all areas of everyday life.

| » next Two cities - two empires |

Two cities - two empires

The territory on which Belgrade and Zemun are located had important strategic, geographic and economic significance since the very beginning. On the crossroads between the West and the East and on the border of middle Europe and the Balkans, both cities had tumultuous histories in which destiny continually joined them together. The Byzantine writer John Kinam wrote that the destinies of Belgrade and Zemun are connected and that they were demolished in turns as though following a certain wheel of fortune so that the stones of one city could be used to build the walls of the other. In the Middle Ages, this territory was the location of the Byzantine and Hungarian battlefields, in which the devastation and turmoil of the Austro-Turkish wars in the 17th and 18th centuries were concluded by the Treaty of Svishtevo in 1791. The armed conflicts of the two great powers on this territory predetermined the destiny of these two cities. The cities changed masters numerous times. These uncertain times were dramatic for the population, which migrated from one city to the other and even further up north with each new treaty.

During the Turkish reign, Zemun stood in Belgrade’s shadow as a small provincial town with an insignificantly developed economy. Following a change of rule (1718 it fell into Austrian hands), crafts and trade suddenly flourished and the greatest contribution to this new development was the separation of Zemun from the Military Border into a free city in 1749. In 1751 the first city hall magistrate was established. These conditions enabled the greater development of crafts and trade.

Following the Treaty of Svishtevo, numerous families from Belgrade received permission from the Austrian authorities to cross over to Zemun. These migrations had a significant impact on the economic and political circumstances in Zemun, which took over the role of Belgrade, especially as far as trade was concerned.

The development of crafts and trade from the mid 18th century created a powerful financial foundation, which made traveling writers regard Zemun as the richest town of the Military Border. Economic development and a lengthy period of peace influenced cultural developments. The second half of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries left a powerful mark on the economic and cultural history of Zemun. The city’s population gradually increased and changed its appearance. A prosperous economic and cultural life was a precondition for the creation of educational and cultural institutions in the city.

| << previous The war times | >> next The military border |

![7. [1760] - Manual for clerks; Language: Turkish, (OZ, K-5/IX, 2)](/cache/thumbs/85c7905bc2cceae78ff20162bfe27a3d.jpg)